what are the names given to each medication listed in the u.s. pharmacopoeia?

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (from the obsolete typography pharmacopœia, significant "drug-making"), in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by the authority of a authorities or a medical or pharmaceutical society.[1]

Descriptions of preparations are called monographs. In a broader sense it is a reference piece of work for pharmaceutical drug specifications.

Etymology [edit]

The term derives from Ancient Greek: φαρμακοποιία pharmakopoiia "making of (healing) medicine, drug-making", a compound of φάρμακον pharmakon "healing medicine, drug, poison", the verb ποιεῖν poiein "to make" and the abstruse noun suffix -ία -ia.[2] [3]

In early modern editions of Latin texts, the Greek diphthong οι (oi) is latinized to its Latin equivalent oe which is in turn written with the ligature œ, giving the spelling pharmacopœia; in modern Uk English, œ is written as oe, giving the spelling pharmacopoeia, while in American English oe becomes e, giving u.s.a. pharmacopeia.

History [edit]

Although older writings exist which deal with herbal medicine, the major initial work in the field is considered to be the Edwin Smith Papyrus in Egypt, Pliny'southward pharmacopoeia.[4]

A number of early pharmacopoeia books were written past Persian and Arab physicians.[5] These included The Canon of Medicine of Avicenna in 1025 Advert, and works by Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) in the 12th century (and printed in 1491),[6] and Ibn Baytar in the 14th century.[ citation needed ] The Shen-nung pen ts'ao ching (Divine Husbandman's Materia Medica) is the earliest known Chinese pharmacopoeia. The text describes 365 medicines derived from plants, animals, and minerals; co-ordinate to legend information technology was written past the Chinese god Shennong.[seven]

Pharmacopeial synopsis were recorded in the Timbuktu manuscripts of Mali.[8]

Red china [edit]

The earliest extant Chinese pharmacopoeia, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing was compiled between 200-250 Advertisement.[9] It contains descriptions of 365 medications.[10]

The earliest known officially sponsored pharmacopoeia was compiled in 659 Advertizing by a team of 23 pharmaceutical scientists led by Su jing during the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) and was chosen the Xinxiu Bencao (Newly Revised Canon of Materia Medica). The work consists of 20 volumes with one defended to the tabular array of contents, and 25 volumes of pictures with one book dedicated to the table of contents. A third part consisting of seven volumes independent illustrated descriptions. The text contains descriptions of 850 medicines with 114 new ones. The work was used throughout China for the next 400 years.[11]

Urban center pharmacopoeia origins [edit]

A dated piece of work appeared in Nuremberg in 1542; a passing student Valerius Cordus showed a drove of medical prescriptions, which he had selected from the writings of the most eminent medical government, to the physicians of the town, who urged him to print it for the benefit of the apothecaries, and obtained the sanction of the senatus for his work. A work known as the Antidotarium Florentinum, was published nether the say-so of the higher of medicine of Florence[1] in the 16th century. In 1511, the Concordie Apothecariorum Barchinone was published by the Social club of Apothecaries of Barcelona and kept in the School of Pharmacy of the University of Barcelona.[12]

Engraved frontispiece of the 1703 Pharmacopoeia Bateana

The term Pharmacopoeia commencement appears as a distinct title in a work[xiii] published at Basel, Switzerland, in 1561 by A. Foes, but does not appear to have come into general use until the beginning of the 17th century.[one]

Before 1542, the works principally used by apothecaries were the treatises on simples (basic medicinal ingredients) by Avicenna and Serapion; the De synonymis and Quid pro quo of Simon Januensis; the Liber servitoris of Bulchasim Ben Aberazerim, which described preparations made from plants, animals, and minerals, and was the blazon of the chemic portion of modern pharmacopoeias; and the Antidotarium of Nicolaus de Salerno, containing Galenic formulations arranged alphabetically. Of this last work, in that location were two editions in use — Nicolaus magnus and Nicolaus parvus: in the latter, several of the compounds described in the big edition were omitted and the formulae given on a smaller scale.[i]

Also Vesalius claimed he had written some "dispensariums" and "manuals" on the works of Galenus. Plainly he burnt them. According to recent research communicated at the congresses of the International Society for the History of Medicine past the scholar Francisco Javier González Echeverría,[fourteen] [xv] [16] Michel De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) also published a pharmacopoeia. De Villeneuve, beau student of Vesalius and the all-time galenist of Paris according to Johann Wintertime von Andernach,[17] published the anonymous " ''Dispensarium or Enquiridion" in 1543, at Lyon, French republic, with Jean Frellon equally editor. This piece of work contains 224 original recipes past De Villeneuve and others past Lespleigney and Chappuis. As usual when it comes to pharmacopoeias, this work was complementary to a previous Materia Medica[eighteen] [19] [20] [21] that De Villeneuve published that aforementioned year. This finding was communicated by the aforementioned scholar in the International Gild for the History of Medicine,[16] [22] with agreement of John M. Riddle, 1 of the foremost experts on Materia Medica-Dioscorides works.

Nicolaes Tulp, mayor of Amsterdam and respected surgeon general, gathered all of his doctor and chemist friends together and they wrote the first pharmacopoeia of Amsterdam named Pharmacopoea Amstelredamensis in 1636. This was a combined endeavor to improve public health afterward an outbreak of the bubonic plague, and likewise to limit the number of dishonest apothecary shops in Amsterdam.

London [edit]

Until 1617, such drugs and medicines as were in mutual employ were sold in England past the apothecaries and grocers. In that year the apothecaries obtained a carve up charter, and it was enacted that no grocer should go on an apothecary's shop. The preparation of physicians' prescriptions was thus confined to the apothecaries, upon whom pressure was brought to bear to make them manipulate accurately, by the issue of a pharmacopoeia in May 1618 by the College of Physicians, and by the power which the wardens of the apothecaries received in common with the censors of the College of Physicians of examining the shops of apothecaries within 7 m. of London and destroying all the compounds which they constitute unfaithfully prepared. This, the commencement authorized London Pharmacopoeia, was selected importantly from the works of Mezue and Nicolaus de Salerno, but it was found to be so full of errors that the whole edition was cancelled, and a fresh edition was published in the following December.[one]

At this period the compounds employed in medicine were often heterogeneous mixtures, some of which independent from 20 to 70, or more, ingredients, while a large number of simples were used in outcome of the same substance being supposed to possess different qualities according to the source from which it was derived. Thus venereal' eyes (i.e., gastroliths), pearls, oyster shells, and coral were supposed to have different properties. Amid other ingredients entering into some of these formulae were the excrements of homo beings, dogs, mice, geese, and other animals, calculi, homo skull, and moss growing on information technology, blind puppies, earthworms, etc.[1]

Although other editions of the London Pharmacopoeia were issued in 1621, 1632, 1639, and 1677, it was not until the edition of 1721, published nether the auspices of Sir Hans Sloane, that any important alterations were made. In this issue many of the remedies previously in use were omitted, although a good number were still retained, such as dogs' excrement, earthworms, and moss from the human skull; the botanical names of herbal remedies were for the first time added to the official ones; the unproblematic distilled waters were ordered of a uniform strength; sweetened spirits, cordials and ratafias were omitted equally well equally several compounds no longer used in London, although still in vogue elsewhere. A corking improvement was effected in the edition published in 1746, in which only those preparations were retained which had received the approval of the majority of the pharmacopoeia committee; to these was added a list of those drugs only which were supposed to be the most efficacious. An attempt was made to simplify farther the older formulae by the rejection of superfluous ingredients.[1]

In the edition published in 1788 the tendency to simplify was carried out to a much greater extent, and the extremely compound medicines which had formed the principal remedies of physicians for 2,000 years were discarded, while a few powerful drugs which had been considered likewise dangerous to exist included in the Pharmacopoeia of 1765 were restored to their previous position. In 1809 the French chemic nomenclature was adopted, and in 1815 a corrected impression of the same was issued. Subsequent editions were published in 1824, 1836, and 1851.[ane]

The outset Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia was published in 1699 and the last in 1841; the first Dublin Pharmacopoeia in 1807 and the last in 1850.[1]

National pharmacopoeia origins [edit]

The preparations contained in these three pharmacopoeias were non all compatible in force, a source of much inconvenience and danger to the public, when powerful preparations such as dilute hydrocyanic acrid were ordered in the one country and dispensed according to the national pharmacopoeia in some other. Every bit a issue, the Medical Human activity of 1858 ordained that the Full general Medical Council should publish a book containing a list of medicines and compounds, to be called the British Pharmacopoeia, which would be a substitute throughout Bang-up Great britain and Republic of ireland for the separate pharmacopoeias. Hitherto these had been published in Latin. The first British Pharmacopoeia was published in the English language in 1864, but gave such general dissatisfaction both to the medical profession and to chemists and druggists that the General Medical Council brought out a new and amended edition in 1867. This dissatisfaction was probably attributable partly to the fact that the majority of the compilers of the work were not engaged in the do of pharmacy, and therefore competent rather to decide upon the kind of preparations required than upon the method of their manufacture. The necessity for this element in the construction of a pharmacopoeia is at present fully recognized in other countries, in most of which pharmaceutical chemists are represented on the committee for the training of the legally recognized manuals.[1]

There are national and international pharmacopoeias, like the Eu and the U.South. pharmacopoeias. The pharmacopeia in the European union is prepared by a governmental organization, and has a specified role in police in the EU. In the U.S., the USP-NF (United States Pharmacopeia – National Formulary) has been issued past a individual non-profit organisation since 1820 under the authority of a Convention that meets periodically that is largely constituted by physicians, pharmacists, and other public health professionals, setting standards published in the compendia through various Skilful Committees.[23] In the U.South. when there is an applicable USP-NF quality monograph, drugs and drug ingredients must conform to the compendial requirements (such as for strength, quality or purity) or be deemed adulterated or misbranded under the Federal food and drug laws.[24]

Supranational and international harmonization [edit]

The Soviet Marriage had a nominally supranational pharmacopoeia, the State Pharmacopoeia of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSRP), although the de facto nature of the nationality of republics within that state differed from the de jure nature. The European Union has a supranational pharmacopoeia, the European Pharmacopoeia; it has not replaced the national pharmacopoeias of EU member states but rather helps to harmonize them. Attempts accept been made past international pharmaceutical and medical conferences to settle a basis on which a globally international pharmacopoeia could be prepared,[1] but regulatory complexity and locoregional variation in conditions of chemist's shop are hurdles to fully harmonizing across all countries (that is, defining thousands of details that tin can all be known to work successfully in all places). Nonetheless, some progress has been made nether the banner of the International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Employ (ICH),[25] a tri-regional organisation that represents the drug regulatory authorities of the European Union, Japan, and the United States. Representatives from the Pharmacopoeias of these three regions accept met twice yearly since 1990 in the Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group to endeavour to work towards "compendial harmonisation". Specific monographs are proposed, and if accepted, go along through stages of review and consultation leading to adoption of a common monograph that provides a mutual ready of tests and specifications for a specific material. Not surprisingly, this is a ho-hum process. The World Wellness Organization has produced the International Pharmacopoeia (Ph.Int.), which does not replace a national pharmacopoeia but rather provides a model or template for i and too can exist invoked by legislation inside a country to serve as that country's regulation.

Medical preparations, uses, and dosages [edit]

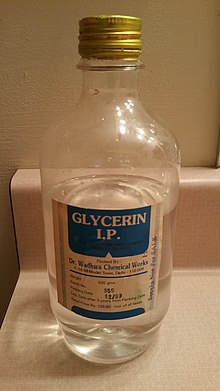

A bottle of glycerin purchased at a pharmacy with the abbreviation I.P. appearing later the product name.

Though formerly printed in that location has been a transition to a state of affairs where pharmaceutical information is available as printed volumes and on the internet. The rapid increase in knowledge renders necessary frequent new editions, to furnish definite formulae for preparations that take already come up into extensive use in medical practise, so as to ensure uniformity of strength, and to give the characters and tests by which their purity and say-so may be determined. However each new edition requires several years to carry out numerous experiments for devising suitable formulae, so that current pharmacopoeia are never quite upwardly to date.[1]

This difficulty has hitherto been met by the publication of such non-official formularies as Squire'southward Companion to the Pharmacopoeia and Martindale: The complete drug reference (formerly Martindale's: the extra pharmacopoeia), in which all new remedies and their preparations, uses and doses are recorded, and in the quondam the varying strengths of the aforementioned preparations in the dissimilar pharmacopoeias are also compared (Squire'south was incorporated into Martindale in 1952). The demand of such works to supplement the Pharmacopoeia is shown by the fact that they are even more largely used than the Pharmacopoeia itself, the first issued in eighteen editions and the second in thirteen editions at comparatively curt intervals. In the UK, the task of elaborating a new Pharmacopoeia is entrusted to a body of a purely medical graphic symbol, and legally the pharmacist does not, reverse to the practice in other countries, have a phonation in the matter. This is nevertheless the fact that, although the medical practitioner is naturally the best judge of the drug or preparations that will beget the best therapeutic result, they are not as competent every bit the pharmacist to say how that preparation can be produced in the almost constructive and satisfactory mode, nor how the purity of drugs can be tested.[1]

The change occurred with the 4th edition of the British Pharmacopoeia in 1898. A committee of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Uk was appointed at the request of the General Medical Council to propose on pharmaceutical matters. A demography of prescriptions was taken to define the relative frequency with which different preparations and drugs were used in prescriptions, and suggestions and criticisms were sought from various medical and pharmaceutical bodies across the British Empire. Equally regards the purely pharmaceutical part of the work a commission of reference in pharmacy, nominated by the pharmaceutical societies of U.k. and Ireland (as they were then), was appointed to report to the Pharmacopoeia Committee of the Medical Council.[one]

Some difficulty has arisen since the passing of the Cariosity of Food and Drugs Act concerning the utilize of the Pharmacopoeia as a legal standard for the drugs and preparations contained in it. The Pharmacopoeia is defined in the preface equally but "intended to afford to the members of the medical profession and those engaged in the grooming of medicines throughout the British Empire one uniform standard and guide whereby the nature and composition of, substances to be used in medicine may be ascertained and determined". It cannot be an encyclopaedia of substances used in medicine, and can exist used only every bit a standard for the substances and preparations contained in it, and for no others. It has been held in the Divisional Courts (Dickins v. Randerson) that the Pharmacopoeia is a standard for official preparations asked for nether their pharmacopoeial proper noun. Simply at that place are many substances in the Pharmacopoeia which are non merely employed in medicine, but accept other uses, such as sulphur, gum benzoin, tragacanth, mucilage arabic, ammonium carbonate, beeswax, oil of turpentine, linseed oil, and for these a commercial standard of purity as distinct from a medicinal ane is needed, since the preparations used in medicine should be of the highest possible degree of purity obtainable, and this standard would exist as well high and too expensive for ordinary purposes. The apply of merchandise synonyms in the Pharmacopoeia, such as saltpetre for purified potassium nitrate, and milk of sulphur for precipitated sulphur, is partly answerable for this difficulty, and has proved to be a mistake, since information technology affords ground for legal prosecution if a chemist sells a drug of ordinary commercial purity for trade purposes, instead of the purified preparation which is official in the Pharmacopoeia for medicinal use. This would not be the example if the trade synonym were omitted. For many drugs and chemicals non in the Pharmacopoeia in that location is no standard of purity that tin be used nether the Adulteration of Food and Drugs Deed, and for these, as well equally for the commercial quality of those drugs and essential oils which are also in the Pharmacopoeia, a legal standard of commercial purity is much needed. This subject formed the basis of word at several meetings of the Pharmaceutical Society, and the results have been embodied in a work called Suggested Standards for Foods and Drugs by C. K. Moor, which indicates the average degree of purity of many drugs and chemicals used in the arts, besides every bit the highest degree of purity obtainable in commerce of those used in medicine.[1]

An important step has as well been taken in this direction by the publication under the authority of the Council of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain of the British Pharmaceutical Codex (BPC), in which the characters of and tests for the purity of many unofficial drugs and preparations are given equally well as the grapheme of many glandular preparations and antitoxins that have come into apply in medicine, but take not yet been introduced into the Pharmacopoeia. This work may as well possibly serve as a standard under the Cariosity of Food and Drugs Act for the purity and strength of drugs not included in the Pharmacopoeia and every bit a standard for the commercial class of purity of those in the Pharmacopoeia which are used for non-medical purposes.[1]

Another legal difficulty connected with modernistic pharmacopoeias is the inclusion in some of them of synthetic chemical remedies, the processes for preparing which have been patented, whilst the substances are sold nether merchandise-marker names. The scientific chemical proper name is ofttimes long and unwieldy, and the doctor prefers when writing a prescription to use the shorter name nether which it is sold by the patentees. In this instance the pharmacist is compelled to employ the more expensive patented commodity, which may lead to complaints from the patient. If the physician were to use the same article under its pharmacopoeial name when the patented article is prescribed, they would become open to prosecution by the patentee for infringement of patent rights. Hence the only solution is for the physician to utilise the chemical name (which cannot exist patented) as given in the Pharmacopoeia, or, for those synthetic remedies not included in the Pharmacopoeia, the scientific and chemic name given in the British Pharmaceutical Codex.[1]

List of national and supranational pharmacopoeias [edit]

In virtually of the New Latin names, Pharmacopoea is the more mutual spelling, although for several of them, Pharmacopoeia is common.

| INN system symbol | Other symbols (including older INN organisation symbol) | English language-linguistic communication title | Latin-linguistic communication title | Other-language title | Agile or retired | Website | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | Brazilian Pharmacopoeia | — | Farmacopeia Brasileira | Active | ANVISA | |

| BP | Ph.B., Ph.Br. | British Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Britannica | — | Agile | BP | |

| BPC | — | British Pharmaceutical Codex | — | — | Retired | — | "BPC" likewise oftentimes stands for "British Pharmacopoeia Commission" |

| ChP | PPRC | Pharmacopoeia of the People'southward Republic of People's republic of china (Chinese Pharmacopoeia) | Pharmacopoea Sinensis | 中华人民共和国药典 | Agile | PPRC | |

| CSL | CSP, Ph.Bs. | Czechoslovak Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Bohemoslovenica | Československý Lékopis | Retired | ||

| Ph.Boh. | Czech Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Bohemica | Český Lékopis | Active | Ph.Boh. | ||

| Slovak Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Slovaca | Slovenský Liekopis | Active | ||||

| Ph.Eur. | EP | European Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Europaea | — | Active | Ph.Eur. | |

| Ph.Fr. | — | French Pharmacopoeia | — | Pharmacopée Française | Active | Ph.Fr. | The name Pharmacopoea Gallica (Ph.Gall.) has not been used since the early on 20th century |

| DAB | — | German Pharmacopoeia | — | Deutsches Arzneibuch | Active | The proper name Pharmacopoea Germanica (Ph.K.) has not been used since the early 20th century | |

| Ph.Hg. | — | Hungarian Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Hungarica | Magyar gyógyszerkönyv | Active | ||

| IP | INDP, Ph.Ind. | Indian Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Indica | — | Active | IP | |

| FI | Indonesian Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Indonesia | Farmakope Indonesia | Agile | FI | ||

| Ph.Int. | IP, Ph.I. | International Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Internationalis | — | Agile | Ph.Int. | |

| F.U. | — | Official Pharmacopoeia of the Italian Commonwealth | — | Farmacopea Ufficiale | Active | F.U. | |

| JP | — | Japanese Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea | 日本薬局方 | Active | JP | |

| JRA | — | Minimum Requirements for Antibiotic Products of Nippon | — | Active | |||

| FEUM | MXP | Pharmacopoeia of the Mexico (Mexican Pharmacopoeia) | — | Farmacopea de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos | Active | FEUM | |

| FP | — | Portuguese Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Lusitanica | Farmacopeia Portuguesa | Active | FP | |

| Ph.Helv. | — | Swiss Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Helvetica | Schweizerischen Pharmakopöe, Schweizerischen Arzneibuch | Active | Ph.Helv. | |

| USP | — | The states Pharmacopeia | — | — | Active | USP | |

| USSRP | — | Land Pharmacopoeia of the Wedlock of Soviet Socialist Republics (Soviet Pharmacopoeia) | — | Retired | |||

| SPRF | — | The State Pharmacopoeia of the Russia | — | Государственная Фармакопея Российской Федерации | Active | SPRF | |

| YP | Ph.Jug. | Yugoslav Pharmacopoeia | Pharmacopoea Jugoslavica | Retired | |||

| RFE | — | Royal Castilian Pharmacopoeia | — | Real Farmacopea Española | Active | RFE |

Run into likewise [edit]

- British Pharmacopoeia

- Erowid

- European Pharmacopoeia

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Homo Use (ICH)

- International Pharmaceutical Federation

- International Plant Names Index

- Japanese Pharmacopoeia

- National Formulary

- Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of Prc

- Specification

- Standards organisation

- The International Pharmacopoeia

- United States Pharmacopeia

- World Wellness Organization

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j yard l one thousand north o p q One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication at present in the public domain:Holmes, Edward Morell (1911). "Pharmacopoeia". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 353–355.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "pharmacopeia". Online Etymology Lexicon.

- ^ φάρμακον , ποιεῖν . Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English language Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ van Tellingen C (March 2007). "Pliny'southward pharmacopoeia or the Roman care for". Netherlands Heart Periodical. 15 (iii): 118–20. doi:ten.1007/BF03085966. PMC2442893. PMID 18604277.

- ^ Philip K. Hitti (cf. Kasem Ajram (1992), Miracle of Islamic Scientific discipline, Appendix B, Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0-911119-43-4).

- ^ Krek, K. (1979). "The Enigma of the First Arabic Volume Printed from Movable Blazon" (PDF). Journal of Well-nigh Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 203–212. doi:x.1086/372742. S2CID 162374182.

- ^ "Classics of Traditional Medicine".

- ^ Djian, Jean-Michel (24 May 2007). Timbuktu manuscripts: Africa's written history unveiled Archived 11 November 2009 at the Wayback Auto. Unesco, ID 37896.

- ^ Lu 2015, p. 63.

- ^ Lu 2015, p. 110.

- ^ "The starting time pharmacopoeia -- Xinxiu Bencao".

- ^ "Museu Virtual - Universitat de Barcelona". world wide web.ub.edu.

- ^ Foes, A (1561). Pharmacopœia medicamentorum omnium, quæ hodie ... officinis extant, etc. Basel.

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Archived 13 Nov 2012 at the Wayback Machine Website with graphical study on the pharmacopoeia Dispensarium past Servetus

- ^ 1998 "The 'Dispensarium' or 'Enquiridion' the complementary work of the Dioscorides, both past Servetus" and "The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his 'Dispensarium'". González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Program of the congress and abstracts of the communications, Eleven National Congress on History of Medicine, Santiago de Compostela, University of Santiago de Compostela, pp. 83-84.

- ^ a b 1998 "The volume of piece of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his Dispensarium"(Le livre de travail de Michel Servet pour ses Dioscorides et Dispensarium) and "The Dispensarium or Enquiridion, complementary of the Dioscorides of Michael Servetus" ( The Enquiridion, L'oeuvre Le Dispensarium ou Enquiridion complémentaire sur le Dioscorides de Michel Servet) González Echeverría, in: Book of summaries, 36th International Congress on the History of Medicine, Tunis (Livre des Résumés, 36ème Congrès International d'Histoire de la médicine, Tunis), 6–eleven September 1998, (two comunicacions), pp. 199, 210.

- ^ 2011 "The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus", (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), Francisco Javier González Echeverría, Francisco Javier, printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra, 607 pp, 64 of them illustrations.pag 194-204

- ^ 1996 " An unpublished work of Michael Servetus : The Dioscorides or Medical Affair from Sesma". González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Panacea Ed. Higher of Doctors of Navarra. Castuera Ed, Pamplona p.44.

- ^ 1996 "Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Affair : an unknown work of Michael Servetus (I)" and " Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Affair: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (II)" González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In : Book of Abstracts. 35th International Congress on the History of Medicine, 2nd-8th, September, 1996, Kos Island, Greece, communications nº: 6 y vii, p. 4.

- ^ 1997 "Michael Servetus, editor of the Dioscorides", González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Plant of Sijenienses Studies "Michael Servetus" ed, Villanueva de Sijena, Larrosa ed and "Ibercaja", Zaragoza.

- ^ 2001 " An owing Spanish work to Michael Servetus: 'The Dioscorides of Sesma' ". González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Varia Histórico- Médica. Edition coordinated by : Jesús Castellanos Guerrero (coord.), Isabel Jiménez Lucena, María José Ruiz Somavilla y Pilar Gardeta Sabater. Minutes from the X Congress on History of Medicine, Feb 1986, Málaga. Printed by Imagraf, Málaga, pp. 37-55.

- ^ 2011 September 9, Francisco González Echeverría VI International Meeting for the History of Medicine, (Southward-11: Biographies in History of Medicine (I)), Barcelona.New Discoveries on the biography of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) & New discoverys on the work of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) Six Meeting of the International Guild for the History of Medicine

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved five Jan 2015.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally title (link) - ^ "USP in Food and Drug Constabulary - U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention". usp.org . Retrieved eighteen January 2017.

- ^ "ICH Official web site : ICH". ich.org . Retrieved eighteen January 2017.

Bibliography [edit]

- Lu, Yongxiang (2015), A History of Chinese Science and Engineering science 2

External links [edit]

- Pharmacopoeial Discussion Grouping

- Medicines Compendium

- Pharma Noesis Park

- Michael Servetus Enquiry Website with graphical written report of the pharmacopoeia Dispensarium past Michael Servetus

- ISHP Working Group History of Pharmacopieas

- Pharmacopoeia, List of Pharmacopeia 2021

plummerupostionots.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmacopoeia

0 Response to "what are the names given to each medication listed in the u.s. pharmacopoeia?"

Post a Comment